NL Journal of Dentistry and Oral Sciences

(ISSN: 3049-1053)

Conceptualising Dental Behaviour Management

Author(s) : Lekshmi Radhakrishnan Suresh. DOI : 10.71168/NDO.02.02.108

In most dental practices, the paediatric age group forms a challenging subgroup of client base owing to numerous factors such as age gap, stage of physical, emotional and cognitive development, communication deficits, lack of familiarity with emotional self-regulation and differing coping strategies, among many others [1,2].

Behaviour management is a key component of paediatric dental practice, (3) requiring a set of highly refined skills that must be developed carefully and patiently over time with a deep understanding of children’s psychological development and how each management technique is expected to function. To this effect, many guidelines and texts have been available throughout the years, being revised to incorporate newer technologies and modifications to older techniques and how best to implement them [3,4,5,6].

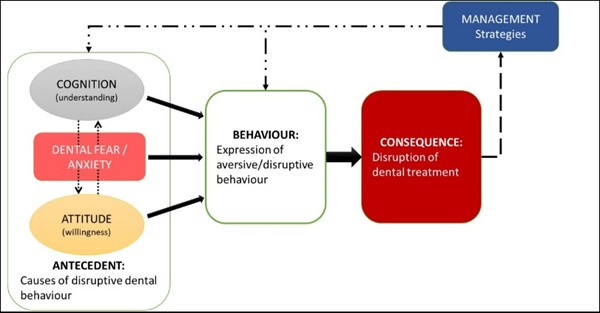

However, as far as understanding the application of the numerous behaviour management techniques is concerned, there has been comparatively less discussion centred on grounding these techniques to a solid foundation of their impact on the child’s state of psychological being. This would allow for some interesting conceptualisations, with one such model being as follows: (Figure 1)

Figure 1: The ABCM model for dental behaviour management. A: Antecedent; B: Behaviour; C: Consequence; M:Management strategies

Developed from the ABC model of cognitive behaviour therapy [7] popularly employed in individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorders [8], the ABCM model for dental behaviour management simplifies the implementation of the various techniques that may be used from a paediatric dentist’s arsenal.

This model allows the practitioner tasked with managing the dental behaviour of a paediatric patient to consider the contributing factors of the child’s behaviour (B), whether within reasonable limits within their capabilities of handling non-pharmacologically or wholly disruptive, forcing the dentist to look back into its antecedents (A), such as the child’s level of cognition, their contributing levels of fear and dental anxiety, and attitude towards the whole experience, dental treatment and the dental team in general. Armed with a reasonable understanding of these factors, the team may then work their way towards establishing a list of behaviour management techniques (M) that would be expected to work for a particular child and at what stage of the treatment, based on careful observation of the patient’s behavioural consequences (C).

On careful analysis of this model, it also becomes interesting to note that basic behaviour management techniques, like tell-show-do, distraction, communication, positive reinforcements, etc., primarily target managing the behavioural antecedents related to the patient’s behaviour (A-B link). This is in contrast to the more advanced behaviour management techniques, such as various sedation techniques, protective stabilisation, hypnosis and general anaesthesia, which are more targeted towards managing their behavioural consequences (B-C link).

Nevertheless, given the ever-growing number of behaviour management techniques, it may be hypothesised that similar applications of various conceptual models may be seen as assistive tools to add to the dental professionals’ understanding of how best to apply them in their paediatric dental practice in the long term.

References

1. Paryab M, Hosseinbor M. Dental anxiety and behavioral problems: A study of prevalence and related factors among a group of Iranian children aged 6-12. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2013; 31: 82–86.

2. Kakkar M, Wahi A, Thakkar R, Vohra I, Shukla AK. Prevalence of dental anxiety in 10-14 years old children and its implications. J Dent Anesth Pain Med. 2016; 16: 199–202.

3. Kohli, N, Hugar SM, Soneta SP, Saxena N, Kadam KS, Gokhale N. Psychological behavior management techniques to alleviate dental fear and anxiety in 4-14-year-old children in pediatric dentistry: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dent Res J. 2022; 19: 47.

4. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Behavior guidance for the pediatric dental patient. The Reference Manual of Pediatric Dentistry. Chicago, Ill.: American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry; 2024: 358-378.

5. Dhar V, Gosnell E, Jayaraman J, et al. Nonpharmacological behavior guidance for the pediatric dental patient. Pediatr Dent 2023; 45: 385-410.

6. Roberts, J.F., Curzon, M.E.J., Koch, G. et al. Behaviour Management Techniques in Paediatric Dentistry. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2010; 11: 166–174.

7. Tiba A. I. The grounded cognition foundation of the first cognitive model in cognitive behavior therapy: implications for practice. Frontiers in psychology. 2024; 15: 1364458.

8. Dyer K. Antecedent-Behavior-Consequence (A-B-C) Analysis. In: Volkmar, F.R. (eds) Encyclopedia of Autism Spectrum Disorders. Springer, New York, NY. 2013

This article licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License CC-BY 4.0., which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are properly credited.