NL Journal of Agriculture and Biotechnology

(ISSN: 3048-9679)

Mitigating Salinity Stress: The Crucial Role of Phosphorus in Plant Adaptation and Productivity

Author(s) : Dr. Binny Sharma*. DOI : 10.71168/NAB.02.06.136

Abstract

Salinity is one of the most serious abiotic stresses limiting global agricultural productivity, particularly in arid and semi-arid regions where soil phosphorus (P) availability is already low. Phosphorus is an essential macronutrient involved in energy transfer, root development, membrane stability, and metabolic regulation, yet its availability is severely constrained under saline conditions due to ionic competition, altered soil chemistry, and reduced mobility. Salinity disrupts P uptake by interfering with phosphate transporter activity, inducing nutrient imbalance, and enhancing P fixation in insoluble forms. Adequate phosphorus supply, however, mitigates the adverse effects of salinity by improving root proliferation, enhancing photosynthetic efficiency, maintaining a favorable K⁺/Na⁺ ratio, strengthening antioxidant defenses, and stabilizing cellular structures. Recent studies highlight strong interactions between P nutrition, ion homeostasis, and stress-responsive gene networks, underscoring the importance of integrated nutrient and stress-management strategies. Sustainable approaches such as P-efficient cultivars, phosphate-solubilizing microorganisms, nano-P fertilizers, soil amendments, and precision fertilization offer promising solutions to enhance P use efficiency and plant resilience in salt-affected soils. This chapter synthesizes current advances in understanding P–salinity interactions and outlines future directions for improving crop productivity under salinity stress. Keywords: Salinity, Phosphorus, Antioxidant defense, Nano- P fertilizers, Phosphate transporter activity.

Introduction

Human population overshoot is closely linked with diminishing resources, loss of biodiversity, ecosystem break- downs, changes in climate, and rising poverty and hunger. Increased population growth threatens both ecologists and agricultural professionals, who face the challenge of maintaining ecological balance while meeting the food needs of large populations. Meeting global food requirements calls for enhancing crop yields and preserving soil fertility, especially by improving the supply of vital nutrients like nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium in agriculture worldwide. Declining soil fertility particularly phosphorus deficiency significantly limits plant growth and crop yields globally, as phosphorus forms a small but essential part of plant biomass [6]. Typically, soils contain about 0.05% total phosphorus, yet only 0.1% of this is accessible to plants. Most soil phosphorus exists in insoluble forms, restricting agricultural productivity on 30–40% of the world’s cultivated lands. Phosphorus availability depends on factors like soil mineral composition, metal oxides (such as calcium, iron, and aluminum), pH level, organic matter, temperature, aeration, and moisture. Reduced phosphorus availability is worsened by increasing salinity a growing issue in arid, semi-arid, and irrigated areas. Each year, about 1.5 million hectares of irrigated land and 1–2% of arid or semi-arid lands become uncultivable due to intense salinity, and if the current trend continues, up to half the world’s farmable land may be affected by salinization by 2050. Therefore, maintaining adequate phosphorus levels in saline soils is a future challenge for agronomists in the future [11].

Phosphorus deficiency caused by salinity, either individually or in combination, is among the key abiotic stresses found in saline agro-ecosystems, which significantly hinder various aspects of plant growth and development including germination, vegetative growth, flowering, fruit formation, and leaf aging, along with core plant metabolic functions such as photosynthesis, respiration, protein creation, and lipid metabolism [3]. Salt stress hampers numerous plant functions such as seed germination, growth of seedlings and roots, development stages, early aging, flowering, and yield, which can ultimately cause early plant death.

In salty conditions, water uptake is reduced, causing osmotic stress due to lowered cell turgor pressure. Plants produce osmoprotectants to combat this stress, although these compounds may not always be adequate. Elevated sodium (Na+) and chloride (Cl−) ions cause ionic stress and disrupt the balance of essential ions, especially the potassium/sodium (K+/Na+) ratio. Plants may alter gene expression to tolerate salt, depending on the degree of salinity and genetic factors. Salinity also interferes with the uptake of key nutrients like nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K+) and promotes oxidative stress by increasing reactive oxygen species (ROS), which can damage plant cells [1]. Salinity impairs plants through two principal mechanisms: initially, it induces osmotic stress that diminishes the roots’ ability to take up water, followed by ionic toxicity that leads to nutrient imbalance, oxidative stress, disrupted hormone levels, and increased vulnerability to diseases. Soil salinization results from the accumulation of various soluble ions, including cations (Na+, K+, Ca2+, Mg2+) and anions (Cl−, NO3−, HCO3−). Based on characteristics like pH, electrical conductivity (EC), and exchangeable sodium percentage (ESP), soils are classified as saline (pH < 8.5, EC > 4 dS/m, ESP < 15), saline-sodic (pH > 8.5, EC > 4 dS/m, ESP > 15), or sodic (pH > 8.5, EC < 4 dS/m, ESP > 15). Salinization can occur naturally through processes like the weathering of minerals or sea level rise (primary salinization), and due to human activities such as improper irrigation, poor drainage, excessive groundwater extraction, unsuitable crop rotations, overuse of agrochemicals, and use of wastewaters (secondary salinization). These elevated salt levels disrupt the plant’s nutritional balance by altering nutrient availability, competitive uptake, transport, or partitioning within the plant, leading to deficiencies in nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium. Specifically, salinity reduces nitrogen availability and nodule formation, limits phosphorus uptake, and hampers potassium transport and absorption, complicating plant nutrition in saline soils. Phosphorus in soil primarily cycles between water and soil, with minimal atmospheric involvement, and exists in three forms based on solubility: insoluble inorganic phosphate, soluble orthophosphate (bioavailable), and insoluble organic phosphate [7]. Insoluble inorganic phosphate occurs as stable primary minerals (like apatites), secondary minerals (such as calcium, iron, and aluminum phosphates), and sorbed phosphorus bound to clay and oxides, while organic phosphorus makes up about 30-65% of total soil P, existing in compounds like inositol phosphates and phospholipids. Phosphorus transitions among these pools through natural physical, chemical, and microbial processes including weathering, adsorption-desorption, dissolution-precipitation, and mineralization. The effect of salinity on phosphorus uptake by plants is complex and conflicting. Studies indicate that adding phosphorus to saline soils improves growth and yield in many crops, but increasing salinity reduces this benefit and does not necessarily enhance salt tolerance. While most research shows salinity decreases phosphorus accumulation in plant tissues, some cases display increased or unaffected phosphorus uptake. This variability suggests that phosphorus supply may either positively or negatively influence salt tolerance, and salt stress can increase, decrease, or have no effect on phosphorus accumulation depending on environmental factors, crop species, genotype, developmental stages, and salinity levels. Additionally, some evidence suggests phosphorus-deficient plants may tolerate salt stress better than phosphorus-sufficient ones in crops like maize and soybean [5,9]. Salinity significantly reduces the bioavailability of phosphorus (P) in soils by influencing both soil chemistry and plant uptake mechanisms. High concentrations of sodium (Na⁺) and chloride (Cl⁻) lead to competitive inhibition at the root-soil interface, where these ions interfere with the absorption of phosphate ions. Salinity also reduces P mobility by decreasing soil water potential, thereby limiting diffusion of phosphate toward the roots. Changes in soil pH under saline–sodic conditions further aggravate P deficiency, as alkaline pH promotes precipitation of P with calcium, magnesium, or sodium compounds. In sodic soils, excessive Na⁺ causes clay dispersion, reducing soil porosity and further constraining P diffusion. Collectively, these factors create an environment where plants experience severe P deficiency despite the presence of adequate total soil phosphorus. Phosphorus uptake under saline conditions is largely hampered by several factors including ionic competition, altered nutrient transport, and changes in soil chemistry. Sodium ions (Na+) compete with vital cations like calcium (Ca2+) and magnesium (Mg2+) required for the proper functioning of phosphate transporters, thereby indirectly inhibiting phosphorus acquisition. Salinity reduces the mobility of phosphorus by decreasing soil hydraulic conductivity and slowing phosphate ion diffusion near the roots. Additionally, saline soils tend to become more alkaline, promoting the precipitation of phosphorus in forms such as calcium phosphate and sodium–phosphate complexes, which are not available to plants. These combined influences significantly curtail phosphorus uptake efficiency, even when fertilizers are applied. Moreover, the adsorption of phosphorus onto soil particles is enhanced in saline soils due to increased ion concentrations, affecting phosphorus availability and transport. Microbial communities and enzymes like alkaline phosphatase can play a role in phosphorus cycling and availability in saline soils, but salinity generally leads to a net decrease in phosphorus bioavailability for plant. Soil phosphorus (P) availability plays a vital role in supporting plant productivity, and soil salinization typically leads to a reduction in plant productivity in terrestrial ecosystems worldwide. However, the exact response of soil P availability to salinity remains unclear, complicating the understanding of how salinization influences plant growth.

A meta-analysis reveals that salinization generally reduces soil total phosphorus and available phosphorus, which correlates with declines in plant productivity across various ecosystems and vegetation types globally. The extent of salinity’s impact on soil P depends on factors like salinity intensity, exposure duration, ecosystem and vegetation type, as well as climate conditions. Effective management practices, including optimizing phosphorus fertilization and selecting appropriate plant species, are essential to improve plant productivity and ecosystem function in salt-affected soils [13,8].

Phosphorus Is a Tricky Nutrient for Plants

Phosphorus (P) is the second most essential macronutrient for plant growth, following nitrogen. It plays a crucial role in various metabolic functions and cellular regulatory processes that depend on phosphorus molecules. Phosphorus forms the structural backbone of vital biomolecules such as ATP, NADPH, nucleic acids, phospholipids, and sugar-phosphates, which are integral to primary and secondary plant metabolism. In soils, total phosphorus content typically ranges from 400 to 1,200 mg per kg, mainly in the form of apatite and other primary minerals. However, less than 0.1% of the total soil phosphorus is present as inorganic phosphate (Pi), the form available for plant uptake, due to its low solubility, slow diffusion, and high soil reactivity. The availability of Pi for root absorption depends heavily on soil factors like ion concentration and pH; in acidic soils, Pi often binds with iron and aluminum, while in calcareous soils, it binds with calcium, making Pi less accessible to plant roots [4].

Phosphorus (Pi) availability in soil is influenced by several physical, chemical, and biotic factors that regulate its dissolution, diffusion, and uptake by plants. Physically, soil texture and moisture play key roles; for example, higher clay content increases Pi retention but reduces its availability in soil solution. Aeration and soil compaction impact oxygen supply and Pi diffusion near roots, while water availability also affects Pi mobility and absorption by plants. Chemically, soil pH, organic matter, redox potential, and concentrations of iron, aluminum, and calcium are crucial. In alkaline soils (pH > 8), calcium reacts with Pi to form insoluble compounds like hydroxyapatite, lowering P availability, while acidic conditions (pH ≤ 5.5) cause Pi to bind with exchangeable aluminum and iron, making it less accessible. Organic matter decomposition enhances P availability by interacting with binding sites and contributing P. Biotic factors include soil microorganisms that facilitate nutrient release and recycling; microbial populations influenced by root exudates can promote Pi solubilization through organic acid production that frees P complexed with metals like Al, Fe, and Ca. Some microbes produce inorganic acids and protons that also help mobilize Pi. Agronomic practices such as legume cover crops and conservation tillage improve P use efficiency by enhancing soil properties, microbial activity, and mycorrhizal colonization. Climate change, through elevated CO2 and temperature, may accelerate P decomposition and affect plant Pi acquisition by altering root morphology, exudation, and microbial interactions, potentially influencing soil Pi availability and ecosystem sustainability [10,2].

Plants’ ability to access soil phosphorus (P) largely depends on their P-acquisition strategies. Nonmycorrhizal plants, like many species in the Brassicaceae and Chenopodiaceae families, can only access P near the root sur- face and are generally found in nutrient-rich, high-P soils. Mycorrhizal plants, which form symbiotic relationships with fungi, access P beyond the root depletion zone, and ectomycorrhizal species can even utilize some organic P and sorbed P through carboxylate release. These plants typically employ a P-scavenging strategy. Nonmycorrhizal plants that exude large amounts of carboxylates and phosphatases can mobilize P sorbed onto soil particles, including organic P, which reflects a P-mining strategy seen in severely P-impoverished soils. Phosphorus uptake is mediated by root phosphate transporter (PHT) proteins which transport inorganic phosphate (Pi) from the soil into plant cells using a proton-coupled mechanism. Under adequate P levels, cytosolic Pi concentrations are high, while under P-starvation, PHT1 transporter genes are often upregulated to enhance uptake, representing a P-starvation response. However, the relationship between Pi transporter expression and actual Pi uptake capacity is complex, and whether expression increases or decreases with P sufficiency varies, necessitating physiologi- cal studies for full understanding. Mycorrhizal fungi can be responsible for a significant portion of P uptake under low P conditions, though their contribution may be limited in severely P-depleted habitats [12]. Elevated levels of sodium (Na⁺) and chloride (Cl⁻) ions suppress the expression and activity of phosphate transporter proteins, particularly in the root epidermis and cortex of plants. These ions disrupt the electrochemical gradient across the plasma membrane, diminishing the proton motive force essential for active phosphate transport. Excess Na⁺ induces oxidative stress and destabilizes membranes, impairing the function of PHT1 phosphate transporters. Additionally, Cl⁻ interferes with cellular signalling pathways that regulate the expression of these transporters. Consequently, the downregulation of phosphate transporters under saline conditions severely limits phosphorus uptake and leads to nutrient imbalances in plants experiencing salt stress. Phosphate-solubilizing microorganisms (PSMs) offer an eco-friendly approach to improving P availability in saline soils. These microbes solubilize fixed phosphorus through the production of organic acids, phosphatases, and proton extrusion mechanisms that lower pH in the rhizosphere. PSMs also enhance root architecture by producing phytohormones such as auxins and cytokinins, improving root surface area and nutrient uptake.

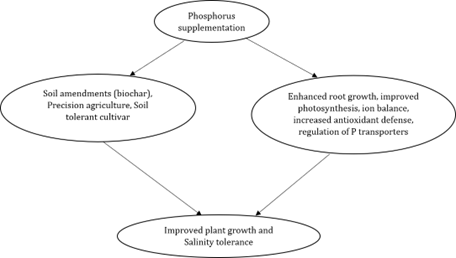

In saline soils, PSMs help alleviate stress by improving microbial activity, enhancing nutrient cycling, and promoting beneficial plant–microbe interactions. Formulating microbial consortia containing P-solubilizers, halotolerant bacteria, and mycorrhizae provides an efficient solution for managing P deficiency in salt-stressed environments. The morphology and architecture of plant roots are critical to their nutrient absorption capabilities, especially for phosphorus (P). Roots are the first plant organs to encounter nutrient availability, and the root system’s spatial configuration directly influences P acquisition. Under P deficiency, many plants adapt by modifying root architecture such as increasing root growth and lateral root formation to better explore soil areas where P is more accessible, often the topsoil where organic matter and P are concentrated. However, responses can vary by species; some plants like Arabidopsis reduce root growth under low P conditions. Adaptive root strategies to low P include increased production of root hairs and cluster roots, enhancing root surface area for better P uptake. Certain root types, such as adventitious roots growing at shallow angles, improve P acquisition efficiency by exploring P-rich surface layers at lower metabolic cost compared to other roots. Adventitious roots can comple- ment basal roots, benefiting overall plant P uptake particularly in soils with stratified P distribution. P signalling mechanisms regulate root development responses, but exact pathways remain partly unclear. Moreover, root exudates like carboxylates and phosphatases can mobilize otherwise inaccessible phosphorus from soil particles, aiding plants in P-deficient or highly sorptive soils. Thus, root architectural plasticity and associated biochemical strategies are essential for optimizing P uptake and plant growth under low availability conditions [14]. Phos- phorus supplementation plays a vital role in mitigating the adverse effects of salinity stress on plants, promot- ing recovery of growth and physiological functions. Adequate phosphorus availability boosts root proliferation, enabling plants to explore more soil volume and enhance nutrient uptake efficiency. It supports photosynthesis by maintaining ATP synthesis, stabilizing thylakoid membranes, and facilitating enzymes involved in carbon fixation, thereby improving photosynthetic rates and chlorophyll content. Phosphorus also aids in maintain- ing ionic balance by improving the potassium-to-sodium (K⁺/Na⁺) ratio, which is crucial for enzyme activity and cell turgor. Furthermore, phosphorus promotes the accumulation of compatible solutes such as proline and glycine betaine, assisting in osmotic adjustment. Enhanced phosphorus status also strengthens the antioxidant defense system by increasing activities of enzymes like superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and per- oxidase (POD), reducing oxidative damage caused by salinity. At the molecular level, phosphorus is crucial in regulating plant responses to salt stress. When plants face combined phosphorus deficiency and salinity, they upregulate genes from the PHT1 phosphate transporter family to enhance phosphate uptake and internal distribution. Salt stress activates genes linked to antioxidant defense, osmotic balance, and membrane transport, helping plants reduce salt-induced damage. There is a significant interaction between phosphorus signaling and hormonal pathways, particularly involving abscisic acid (ABA) and ethylene, which coordinate stress-response gene networks. This molecular crosstalk enables balanced regulation of growth, nutrient homeostasis, and stress tolerance, allowing plants to adapt effectively under saline conditions.

Efficient phosphorus management is crucial for maintaining crop productivity in saline soils. Using appropriate phosphorus fertilizers like DAP, SSP, and TSP at suitable rates and placements improves nutrient availability and uptake. Advanced fertilizer types such as nano-phosphorus and polymer-coated slow-release formulations enhance phosphorus use efficiency by minimizing fixation and ensuring sustained nutrient release. Combining phosphorus fertilization with soil amendments like gypsum, biochar, and organic matter enhances soil structure, reduces sodicity, and promotes nutrient mobility. Proper irrigation scheduling and fertigation techniques further optimize phosphorus delivery to plants. Additionally, foliar phosphorus sprays can quickly address deficiencies during critical growth phases under salinity stress, providing an extra strategy for maintaining plant health and productivity.

Phosphorus (P) interacts positively with other essential nutrients such as nitrogen (N), potassium (K), and sulfur (S) under saline conditions, enhancing plant salt tolerance. Adequate P availability improves nitrogen assimilation and supports potassium retention, which helps maintain ionic balance critical for plant function under salt stress. Together, phosphorus and sulfur contribute to energy metabolism and protein synthesis. However, excessive sodium (Na⁺) in saline soils can antagonize the uptake of phosphorus and other cations. Therefore, balanced fertilization that considers nutrient interactions is essential for optimizing phosphorus use efficiency and improving plant resilience to salinity. Studies show that P fertilization increases plant growth and nutrient uptake under salinity stress by improving the K⁺/Na⁺ ratio, photosynthetic performance, and accumulation of osmoprotectants, thereby mitigating salt stress effects and enhancing overall plant health and productivity. Gen- otypic variability in P-use efficiency and salt tolerance offers opportunities for breeding resilient crop varieties. Screening and identification of genotypes with high P acquisition efficiency, superior root traits, and salt-tolerant physiological mechanisms are crucial steps toward genetic improvement. Modern breeding tools such as mark- er-assisted selection and QTL mapping help identify genomic regions associated with P efficiency under salinity stress. Gene-editing tools like CRISPR/Cas enable precise modification of genes governing P uptake, transporter activity, and ion homeostasis, accelerating the development of crop varieties capable of thriving in saline soils.

Soil and rhizosphere engineering approaches can significantly enhance phosphorus availability and plant resilience under salinity. The incorporation of biochar, compost, and organic matter improves soil structure, increases water retention, and enhances microbial activity, all of which contribute to higher P mobility. Plants can also be engineered or selected to modify root exudates that stimulate P solubilization and foster beneficial microbial communities. Additionally, using salt-tolerant rootstocks and grafting techniques provides a practical method to enhance nutrient uptake and salt tolerance, enabling crops to perform better in challenging saline environments.

Effect of phosphorus supplementation in enhancing plant growth and salinity tolerance

Conclusion

Salinity stress is a major environmental factor that limits agricultural productivity, especially in arid and semi-arid regions. Phosphorus (P), an essential macronutrient, plays a crucial role in enhancing plant tolerance to salinity by supporting root growth, energy metabolism, membrane stability, and maintaining ionic balance. Adequate P nutrition enables plants to sustain better physiological functions, reduce ion toxicity effects, and improve overall growth and yield in saline conditions. Effective management combining P fertilization with salt-tolerant crop cultivars and optimized agronomic practices is a practical strategy to maintain crop productivity in salt-affected soils. Looking ahead, precision agriculture advancements can optimize P fertilizer timing, form, and dosage to improve nutrient use efficiency in salt-stressed crops. Breeding and biotechnological tools such as gene editing can develop varieties with superior P-use efficiency and salt tolerance by targeting genes involved in P uptake and signalling pathways. Innovations in slow-release nano-P fertilizers and phosphate-solubilizing microorganisms offer eco-friendly solutions to enhance P availability in saline soils. Manipulating root architecture and beneficial microbes in the rhizosphere can improve P acquisition and mitigate salt-induced nutrient imbalances. Integrative physiological, biochemical, and omics-based approaches can deepen understanding of P–salinity interactions and aid early stress detection and optimization. Long-term field trials across diverse climates are essential to validate lab findings and develop region-specific recommendations for salt-affected agriculture.

References

- Acharya BR, Gill SP, Kaundal A, Sandhu D. Strategies for combating plant salinity stress: The potential of plant growth-promoting microorganisms. Front Plant Sci. 2024;15:1406913.

- Ainsworth EA, Long SP. 30 years of free-air carbon dioxide enrichment (FACE): What have we learned about future crop productivity and its potential for adaptation? Glob Change Biol. 2021;27(1):27–49.

- Atta K, Mondal S, Gorai S, Singh AP, Kumari A, Ghosh T, Roy A, Hembram S, Gaikwad DJ, Mondal S, Bhattacharya S, Jha UC, Jespersen D. Impacts of salinity stress on crop plants: Improving salt tolerance through genetic and molecular dissection. Front Plant Sci. 2023;14:1241736.

- Bechtaoui N, Rabiu MK, Raklami A, Oufdou K, Hafidi M, Jemo M. Phosphate-dependent regulation of growth and stress management in plants. Front Plant Sci. 2021;12:679916.

- Cosse M, Seidel T. Plant proton pumps and cytosolic pH-homeostasis. Front Plant Sci. 2021; 12:846.

- Dey G, Banerjee P, Sharma RK, Maity JP, Etesami H, Shaw AK, Huang YH, Huang HB, Chen CY. Management of phosphorus in salinity-stressed agriculture for sustainable crop production by salt-tolerant phosphate-solubilizing bacteria-A review. Agronomy. 2021;11(8):1552.

- Faucon MP, Houben D, Reynoird JP, Mercadal-Dulaurent AM, Armand R, Lambers H. Advances and perspectives to improve the posphorus availability in cropping systems for agroecological phosphorus management. Adv Agron. 2015;134:51–79.

- Goyal V. Promoting sustainable agriculture: Approaches for mitigating soil salinity challenges—A review. Agric Rev. 2025;46(3).

- Irfan M, Aziz T, Maqsood MA, Bilal HM, Siddique KHM, Xu M. Phosphorus use efficiency in rice is linked to tissue-specific biomass and P allocation patterns. Sci Rep. 2020;10:4278.

- Jia Y, Kuzyakov Y, Wang G, Tan W, Zhu B, Feng X. Temperature sensitivity of decomposition of soil organic matter fractions increases with their turnover time. Land Degrad Dev. 2020;31(6):632–645.

- Kumar P, Sharma PK. Soil salinity and food security in India. Front Sustain Food Syst. 2020; 4: 533781.

- Lambers H. Phosphorus acquisition and utilization in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2022;73(1):17–42.

- Li M, Petrie MD, Lü X, Wang J, Sun X, Hu N, Chen H. Salinization decreases soil phosphorus availability and plant productivity in terrestrial ecosystems. Earths Future. 2025;13(9):e2024EF005738.

- Peret B, Desnos T, Jost R, Kanno S, Berkowitz O, Nussaume L. Root architecture responses: In search of phosphate. Plant Physiol. 2014;166(4):1713–1723.

This article licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License CC-BY 4.0., which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are properly credited.